Alternative Futures: Questioning Design Standards

September 11, 2023

Published in Schneiderman, Deborah, Anca I. Lasc, and Karin Tehve, eds. Appropriated Interiors. New York: Routledge, 2022.

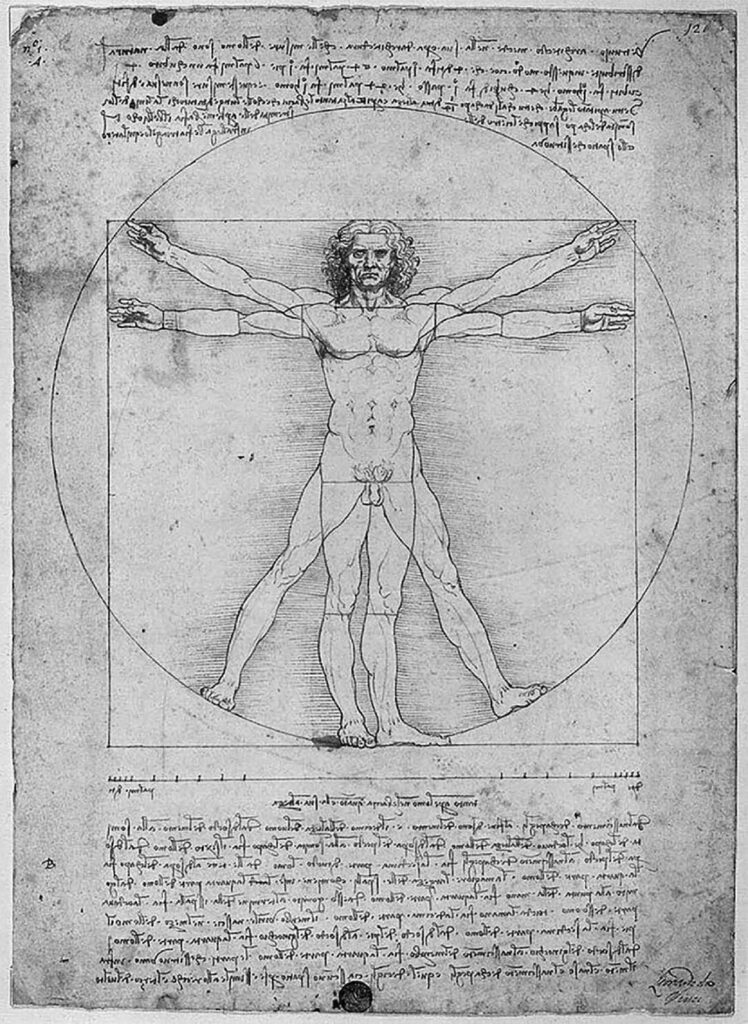

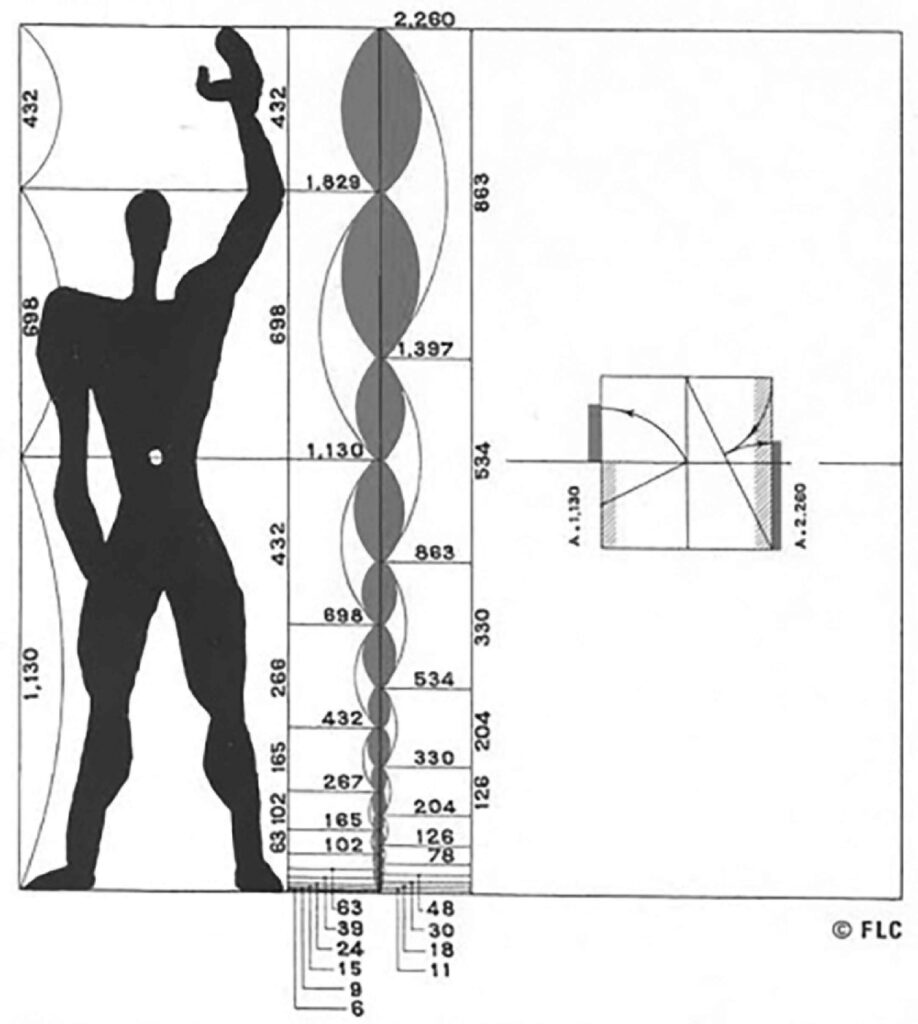

Since antiquity, Western architects have presumed that the user of the designed environment is a prototypical body, one who is by default white, able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual and male. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Le Corbusier’s Modulor Man are only two examples of how architects have designed buildings based on the proportions of an “ideal” male body, one that people could aspire to but only approximate. However, by the turn of the 20th century, the notion of the “ideal” body that had formed the basis of the Western architectural tradition since the Renaissance gave way to a new conception: the “normal” or “average” body, one whose anatomical characteristics performing a range of tasks could be studied and measured using two techniques adopted by architects and designers—anthropometry and ergonomics.

These concepts were applied by capitalists to maximize workplace efficiency and by adherents of suspect ideologies like eugenics, a movement that emerged in Europe and the United States in the early decades of the 20th century dedicated to “scientific racism”—improving the human race by selectively breeding those with positive rather than negative genetic traits. In the name of science, these findings were enlisted to rationalize state-sponsored discrimination. So- called abnormal people were denied citizenship and voting rights and subjected to anti-miscegenation laws and sterilization based on the belief that nonnormative bodies belonging to women, people of color, immigrants and the disabled possessed innate physical or mental defects that rendered them misfits and, as a consequence, unfit to participate in the American public realm.

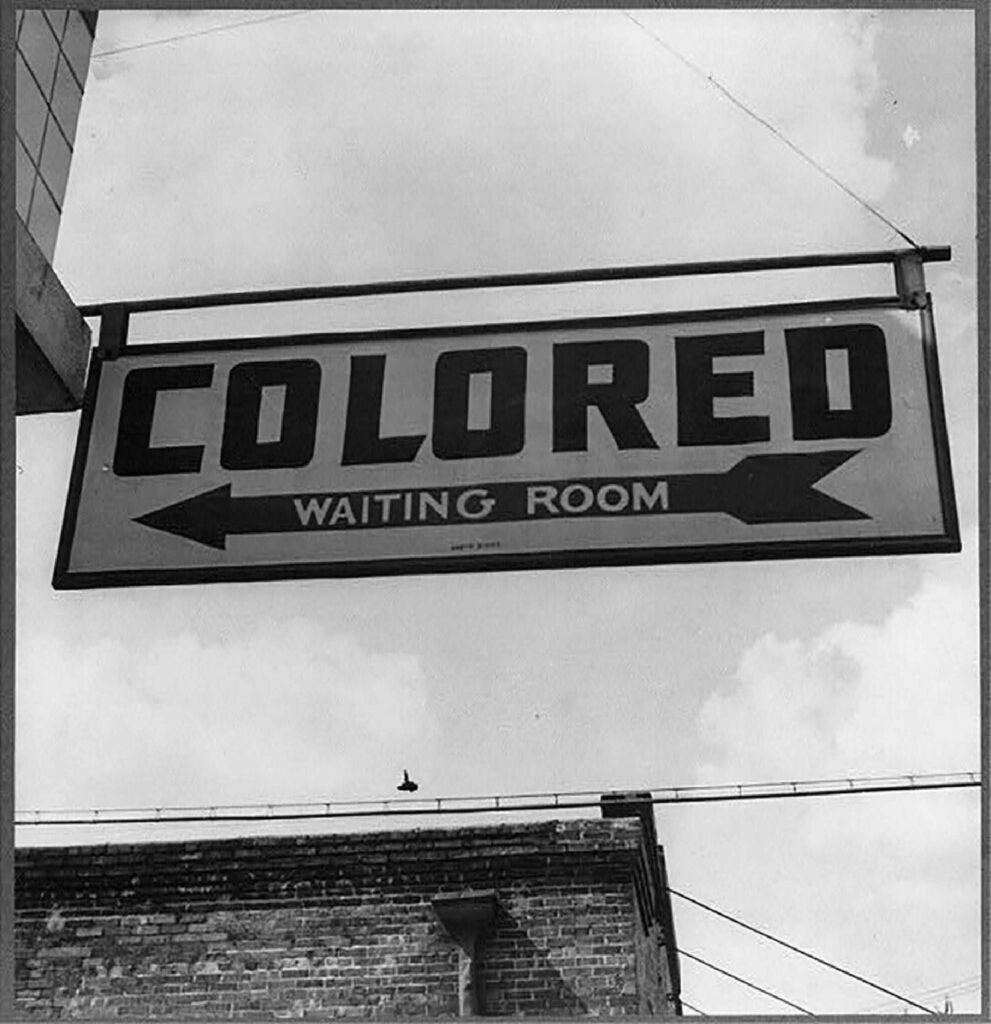

Racist, sexist and ableist thinking exemplified in movements like eugenics had spatial implications, restricting who was included and excluded from American public space at a range of scales.1 Sometimes these tactics were manifested in legislation like Jim Crow laws that mandated racial segregation in public restrooms, trains and restaurants from 1865 to 1965 and the Immigration Act of 1924, put in place to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity that until 1952 denied Asians, Italians, Jews and Eastern Europeans from setting foot on US soil. However, more often than not, the construction of inaccessible spaces that excluded “undesirable” citizens was made possible through the implementation of design conventions, often enforced by building codes, that were passively accepted by architects and designers, many of which we have inherited to this day. Consider the steps leading to the entrances of public buildings elevated on podiums that make the transition between sidewalks and streets difficult to traverse for the elderly and people with mobility and sensory disabilities; sex-segregated facilities like restrooms, locker rooms and military barracks that discourage trans and nonbinary people from using them; border walls that prevent immigration into the southern United States; or substandard housing projects that work in conjunction with redlining to perpetuate structural racism and feed the prison industrial complex that disproportionately incarcerates Black men.

Unfortunately, these practices are not a thing of the past. The Black Lives Matter movement and the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable communities have underscored the urgency for architects and designers to own up to our historical complicity in perpetuating structural racism, heteronormativity and ableism in America through design. In the name of social equity, we must become design activists, committed to inventing alternative modes of professional practice that will allow us to combat these strategies of inclusion and exclusion that are enacted through the protocols of professional practice that we take for granted.

In 2015, design activism led me to establish a new branch of my architectural studio, MIXdesign, a think tank and inclusive design consultancy dedicated to combating architecture’s indifference to the needs of what we call “noncompliant bodies”—people of different ages, genders, races, faiths and abilities that fall outside the cultural mainstream. We work with progressive clients to develop toolkits, recommendations and prototypes for making everyday building types— like restrooms, campuses, museums and residential spaces—safe and accessible for a wide spectrum of people with different identities and embodiments. Our intersectional approach is based on the conviction that human experience and embodied identities are constituted by a variety of interconnected factors, including age, gender, race, culture, religion and ability.

Our overall objective is to design public spaces that promote sharing among individuals, friends, families and caregivers while recognizing that there are no universal solutions. For each project, our goal is to allow the maximum number of differently embodied and identified people to mingle while providing accommodations for end users who have unique privacy or functional needs. Hence, our name: MIXdesign. We believe that looking at the world through the lens of noncompliant bodies will allow designers to not only create spaces responsive to their needs but also spawn design innovations that will enhance every-body’s experience.

Figure 1: This ideal is illustrated by Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, a pen-and-ink drawing of 1487 depicting a white youth whose outstretched arms and legs conform to the circumference of a circle and a square.

Figure 2 Le Corbusier’s Modulor Man.

To accomplish our mission, MIXdesign has been developing an inclusive design methodology that is the subject of this paper. It is predicated on interrogating and then offering alternatives to formulaic architectural conventions that unwittingly encode prevailing racist, heteronormative and ableist ideologies that perpetuate the status quo. This essay treats MIXdesign’s first and ongoing project, Stalled!, as a case study to elaborate our design process. Launched in 2015, Stalled! takes as its point of departure American debates surrounding transgender access to public restrooms to address an urgent social justice issue: the need to create safe, sustainable and inclusive public restrooms for everyone regardless of age, gender, race, religion and disability. As a typology that bridges allied fields— architecture, interiors, product design, planning and engineering—restrooms are an ideal lens through which to examine how design professionals are responsible for maintaining problematic cultural assumptions about the nature of human embodiment and identity through the procedures and practices that govern the design disciplines.

The organization of this essay follows the structure of the inclusive design methodology that informed the development of Stalled!. It consists of two parts, phase 1.0, Cross-Disciplinary Research through a Historical Lens, as a prerequisite for phase 2.0, Design Prototyping and Engagement 2 Our design approach builds upon, but in some important respects differentiates itself from, the work of our colleagues who also begin projects by studying the particular typology they are working on. Like them, we conduct literature reviews and comb through up-to-date sources to familiarize ourselves with the range of programmatic, legal, technical and environmental variables necessary for delivering a successful project. This entails consulting a range of information, including books, manuals and design guidelines, as well as codes that govern the programmatic technological and legal variables associated with a building type.

However, rather than accept these professional resources at face value, we examine them through a critical transdisciplinary and transhistorical lens. This approach is based on our strongly held conviction that the performance of embodied human identity takes place within familiar architectural “types”— ordinary structures categorized by use and associated with specific activities that distribute bodies within formulaic spatial configurations. These shape the way humans interact with each other and the world around them. However, MIXdesign rejects this concept of typology (founded by 18th-century neoclassical architects like Durand and inherited by such 20th-century architects as Aldo Rossi), which considers building types as timeless, transhistorical structures. In a similar vein, we reject the still-prevailing functionalist conception (endorsed by modernists like Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos) which considers types like bathrooms to be shaped by objective physiological and technological factors. Instead, we treat typologies as well as the guidelines and codes that describe them as historically contingent formal constructs shaped by the interplay of changing social, political, economic and environmental forces that perpetuate the dominant ideologies and values of those in power. Nevertheless, we believe that architects and end users can, through critical analysis, contest, modify or jettison these outmoded norms as a means to reinvent new unforeseen spatial configurations that allow a diverse range of differently embodied and identified people to productively perform activities as they interact in public and private space. This conviction is the guiding premise that drives all of our projects, including Stalled!.

Phase 1.0: Cross-Disciplinary Research through a Historical Lens

In 2015, my architectural design studio JSA/MIXdesign was invited to design the NYC headquarters for GLSEN (the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network), a nonprofit dedicated to making schools safe and nurturing environments for K–12 students. Building codes coupled with an uncooperative landlord prevented us from implementing the “gender neutral” bathrooms requested by our clients. At the same time staff at my architectural studio were confronting these work-related obstacles, I was following media coverage of national debates triggered by transgender people using public bathrooms. I reached out to Susan Stryker, a leading transgender historian, theorist and activist whom I had met at UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design over ten years earlier. Our informal dialogue initially conducted over email and phone led us to co-author an essay published in the South Atlantic Quarterly , which grew into Stalled!, an ongoing design/research initiative. Early on, Susan recruited legal scholar Terry Kogan to join our team. Over the years, Stalled! has since expanded to include Seb Choe, an inclusive design activist; Quemuel Arroyo, disability specialist; and Antonia Caba, formerly of Yale School of Public Health, as well as a wider network of experts and consultants.

American Restroom Politics 1880-2021

Susan, Terry and I began the Stalled! initiative by getting a thorough understanding of the trans restroom battles that were being waged across the United States. It seemed to us that the panic over the presence of transgender people in sex-segregated public toilets was part of a long-simmering partisan reaction to overlapping cultural and political events that were taking place at that time. They included the Supreme Court approval of same-sex marriage in 2015 and the 2016 Obama administration Title IX guidelines clarifying that the federal law banning sex discrimination in education programs and activities also protects students who are transgender. It also included an unprecedented cultural visibility for trans people in the mainstream media. This increased recognition and federal acceptance of trans people was met with considerable backlash.

A high-profile example is North Carolina’s House Bill 2, which mandated that sex-segregated restrooms be used according to the sex designated on a person’s birth certificate. Since we launched Stalled! in 2015, more than two dozen similar bills attempting to restrict gender-appropriate public toilet access for transgender people have been introduced in statehouses across the United States. When Trump assumed the presidency in 2017, his administration supported these efforts by withdrawing transgender-supportive interpretations of existing laws put forth by the Obama administration, including Obama-era Title IX guidelines as well as a series of policies that effectively erased federal recognition of LGBTQ people.3 During the time of this writing in the early days of the Biden administration, battlegrounds continue to be tangible architectural sites like restrooms.

Rather than looking at contemporary bathroom politics in isolation, the Stalled! team took a broader view and looked at them within a historical context. We quickly discovered that bathroom debates are not new. At different moments in US history, the public bathroom has registered anxieties triggered by the threat of previously marginalized groups moving into mainstream society.

Milestones include the creation of the “ladies’ room” as more women entered the paid workforce in the 1880s. Naysayers argued that if women were to leave the security of their homes, their mere presence in the workplace, previously an exclusively male domain, would be catastrophic. Women were considered physically and mentally weak. They would be vulnerable to male workers, who would find their presence a distracting temptation. In response to these claims, workplaces, like offices and factories, needed to offer women a home-like space as a refuge from the aggressive public male sphere. This special accommodation took the form of the first sex-segregated bathrooms (Figure 3), even though until that time men and women had shared unisex privies, typically freestanding outhouses.4

Figure 3 A women’s restroom in a Pittsburgh factory, photograph, 19th century.

Figure 4 A segregated waiting sign at a bus stop in Georgia, photograph, Library of Congress, 1943.

During the 1950s and 1960s, bathrooms were again a battleground in the fight to abolish “colored” bathrooms (Figure 4) during the civil rights movement. Jim Crow laws mandating bathroom segregation were based on long-standing arguments that were previously used to defend slavery and white supremacy. It was argued that African Americans, arrested in their evolutionary development, were bestial. Believed to be mentally inferior and physically unclean, they posed health and safety risks to whites, especially white women. Adding insult to injury, Jim Crow laws not only mandated that Black people be banned from sharing bathrooms with white people but also forced Black men and women to use one small, often filthy space, thus effectively denying Black people the privacy between the sexes, which opponents of all-gender restrooms argue is a “natural” right of humans.

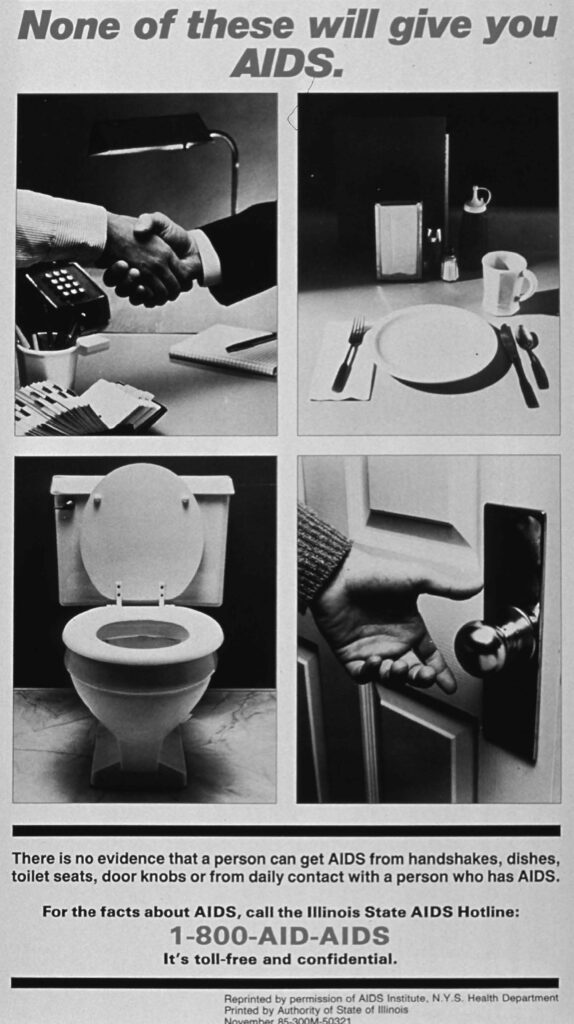

During the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s, restrooms again incited unsubstantiated fears, this time that straight men would be infected with HIV by sharing public toilets with gay men. Similar to Black men during Jim Crow, gay men were also portrayed as disease carrying and promiscuous. Now straight men, as opposed to women, were presented as defenseless victims. The men’s room was condemned as a germ-infested place where men could become infected by touching contaminated toilet seats and restroom fixtures, even after science confirmed that AIDS was only transmitted through the direct exchange of bodily fluids during sex. Making matters worse, men’s rooms were portrayed as notorious cruising grounds where gay men threatened to prey upon and corrupt straight men, compromising the health, safety and morality of the male body politic (Figure 5).

Figure 5 “None of These Will Give You AIDS” poster, New York State Department of Health, 1987.

In a similar vein, the disability rights movement demanded accessible public space, including restrooms. Obstacles included the engrained perception that the disabled possessed shameful physical and mental defects that required them to be sequestered in hospitals and, in some cases, sterilized by eugenicists in the name of social engineering. Beginning in the 1960s, activists mobilized to counteract these negative stereotypes and demand equitable access to spaces and services. The disability rights cause was reinforced by a shift in perception disseminated in the mass media following World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War, when injured veterans were no longer portrayed as deviants but as patriots. Society was obligated to honor the sacrifices of those they previously shunned, providing disabled veterans with medical care and educational opportunities to integrate them back into mainstream society.5 Thirty years of grassroots activism, including events like The Capitol Crawl (Figure 6), inspired by tactics learned from the civil rights movement and strengthened by alliances with organizations like the Black Panthers, finally led to the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

Figure 6 “Capitol Hill Crawl” photograph, Tom Olin, 1990.

The transgender bathroom debate is just the latest episode in this long history. In 2015, Campaign for Houston, a conservative group opposed to a proposed anti-discrimination ordinance, aired an infomercial that tapped into anxieties stirred by the prospect of trans people using public restrooms. Filmed in black and white, the political campaign, which masquerades as an infomercial, borrows from the language of horror films to describe the actions of a male stalker: an anonymous man enters a women’s room, washes his hands and hides in a stall until the arrival of his prey—a young white girl wearing a skirt. The clip ends with the frightened gaze of the unsuspecting victim looking up at her presumed assailant, who follows her into the toilet stall. The infomercial builds suspense through point-of-view shots that alternate between close-ups of the sex offender’s body seen in fragments (the back of his head, hands and feet) and cropped images of the bathroom fixtures he interacts with (ceiling light, dripping faucet, drain, paper towel dispenser and toilet stall) (Figure 7). Meanwhile, we listen to the female voice of a narrator whose cautionary words are overlaid in large capital letters over the screen.

Houston’s Proposition One Bathroom Ordinance: What does it mean to you? Any man at any time could enter a women’s bathroom simply by claiming to be a woman that day. No one is exempt. Even registered sex offenders could follow women or young girls into the bathroom, and if a business tried to stop them, they’d be fined. Protect women’s privacy. Prevent danger. Vote No on the Proposition One Bathroom Ordinance. It goes too far.

This informercial achieved its goal. The anti-discrimination law that was intended to protect the rights of all Houston citizens was defeated by singling out trans people and misrepresenting them as male perverts who stalk girls in the ladies’ room. Evidence-based statistics show that these claims are unsubstantiated: trans people—trans women of color in particular—are the likelier victims of restroom harassment and assault.6

Figure 7 Stills from Campaign for Houston commercial (0:33) (0:26), YouTube, uploaded 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7thOvSvC4E&ab_ channel=CampaignforHouston.

Today, bathroom battles similar to the 2015 Houston Campaign continue. Yet again, the public restroom (by virtue of it being a physical space) transforms an abstract concern into a tangible peril and becomes the setting for nightmarish fantasies of “normal” citizens put at risk by physically interacting with “abnormal” people in public space. Again, unfounded fears are defended by enlisting variations of long-standing and recurring themes that falsely portray trans people—like women, Blacks and gay men before them—as infectious sexual predators who threaten the safety, health and morality of mainstream society through physical proximity in the public realm. However, not only do trans restroom debates dredge up long-standing fears and prejudices, they add a new one to the list—gender nonconformity. The authors of Stalled! believe that what some people find so threatening about trans people is that they call into question the idea that one’s gender is determined by anatomy and made manifest in sex-segregated spaces like bathrooms mandated by law. Trans, nonbinary, intersex and other gender-nonconforming people demonstrate there are many ways of expressing one’s gender that are independent from biological sex and don’t conform to the binary of sex-segregated bathrooms.

Bathroom Design History: Roman Antiquity to Modernism

Looking at trans debates in their political and historical context gave us a broader perspective that allowed Stalled! to call into question the way bathroom politics were myopically and inaccurately framed as a question of safety alone. This wider view prepared us to turn our attention to another aspect of the controversary that had been overlooked in the volumes of commentary about trans access to bathrooms written by politicians, lawyers and journalists—the physical space of the sex-segregated restroom itself.

We began by conducting an in-depth spatial and cultural analysis of generic public restrooms. We studied the illustrated manuals that professionals typically consult to create code-compliant restrooms, such as Architectural Graphic Standards, as well as resources like ADA guidelines and building codes. Without exception, these documents illustrate restrooms using austere black-and-white plans and elevations annotated with ergonomic dimensions. Usually, these single-line drawings include robotic human figures of men and women to depict the range of motion required to perform bathroom functions. The only concession to nonnormative bodies are ADA diagrams illustrating the circulation path and turning radius of a person—generally male—in a wheelchair.

We found that these seemingly neutral technical diagrams are predicated upon a series of erroneous cultural assumptions that shape bathroom design: they reinforce the tacit assumption that the design of restrooms, like other building types, is solely shaped by functional parameters determined by human anatomy, technology and infrastructure (plumbing and sanitation systems) whose inevitable outcome yields a single universal prototype, a configuration that sorts human beings into two categories—men and women—that need to be separated from one another. In this way, professional resources implicitly reproduce two interdependent and highly problematic cultural assumptions about gender: first, a “biological” conception of gender based on the notion that there are only two genders, male and female, and second, that these two genders need to be divided from one another in different rooms based on the notion of a universal need for privacy between the sexes that underpins legal arguments, including the case opposing all-gender restrooms that was meant to be heard before the Supreme Court.

However, the next step in our process—tracing the evolution of restrooms through the lens of architectural history—would allow us to test the validity of these tacit assumptions governing restroom design. There is a vast literature devoted to the history of bathrooms that traces their evolution, primarily from an Anglo-American perspective. A wide range of authors representing different fields—from architectural history to psychoanalysis—have explored this rich territory from a variety of theoretical, social, economic and technological perspectives. The following condensed survey of Western bathroom history from antiquity to today challenges our preconceptions about the formal and ideological underpinnings of this ostensibly timeless typology as encoded in architectural standards.

We take for granted that bathrooms, by necessity, combine in one space three activities—washing, eliminating and grooming—which history shows were separated from one another until the advent of water-delivery systems in the 19th century.7 From antiquity to the Middle Ages, washing and eliminating were communal activities conducted in separate locations. Romans washed in lavishly appointed public baths that some archeologists believe might have been used by men and women. Romans of all ages defecated in communal latrines that many archeologists conjecture might, in some instances, have been unisex. People sat on continuous wood or stone benches while engaged in conversation. One surviving mural depicts philosophers engaged in an impassioned debate while defecating.

During the Middle Ages, washing and eliminating were class based. Kings and knights bathed in individual tubs while commoners visited co-ed public bathhouses where men and women bathed and sometimes dined together in communal tubs, often perfumed with herbs and spices. Likewise, the nobility defecated in chamber pots cleaned by servants while commoners used communal unisex facilities that discharged waste into tanks cleaned by waters from the castle moat or through holes inserted in urban bridges that deposited human waste into the rivers below.

However, attitudes about restrooms changed during the Enlightenment, with the emergence of bourgeois values about privacy. Etiquette manuals discouraged conversation with people squatting in the street. For the first time, body parts and their byproducts needed to be hidden. By the 19th century, people became ashamed about urinating and defecating in public, especially in view of members of the opposite sex. They also became uncomfortable about coming into contact with their own and other people’s waste and bodily fluids. Theorists of abjection, like Julia Kristeva, Mary Douglas and Elizabeth Grosz, argue that abject substances like blood, feces and urine discharged from human orifices contradict the reassuring fiction that the human skin is an effective membrane that allows us to differentiate and control the relationship between ourselves and the outside world. Abject substances are painful reminders that we are mortal beings, made of flesh and blood, prone to deterioration, decline and death.8

However, two 19th-century technological advances—the advent of underground sanitation systems coupled with mass-produced plumbing fixturesallowed “mankind” to triumph over abjection through waste management. Modern architects like Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos famously championed plumbing: running water connected to toilets and sinks eliminated the sight and smell of waste. Their impervious porcelain surfaces were rendered in white, which conveys the reassuring visual impression of cleanliness.9

Affordable manufactured plumbing fixtures serviced by public sanitation systems resulted not only in the birth of the domestic bathroom but also made possible another significant development: the emergence of the first sex-segregated restrooms in the United States. Terry Kogan describes how American bathroom design was shaped by a “separate spheres” ideology that confined women, considered the “weaker sex,” to the home while men, physically and intellectually stronger, were free to occupy public space. Men and women alike used privies, freestanding wooden enclosures typically located in domestic backyards. Some were single user, while others accommodated multiple family members, sometimes of both sexes, who eliminated together. However, by the mid-19th century, women were increasingly leaving home to take part in public cultural and retail activities as well as to work. According to Kogan, men threatened by this challenge to patriarchy argued that this would adversely impact women’s health and well-being. In response, architects introduced women-only spaces, like parlors and sex-segregated restrooms, in libraries, hotels, department stores and factories, conceiving of them as safe havens that protected vulnerable females from the pressures of the male public realm.10

These milestones of bathroom history from communal Roman and medieval bathhouses and latrines to unisex American backyard privies proved that the sex-segregated restroom we take for granted is not an inevitability. Historical precedents refute the prevailing wisdom, reproduced in architectural standards and legal bathroom battles, that the configuration of separated men’s and women’s rooms answers to universal standards of privacy needed to be maintained between two genders, categorized by anatomical difference.

Phase 2.0: Design

Prototyping

Design history proved liberating. Stalled!’s exploration of Western bathroom permutations convinced us that we need not be limited by convention. Now we were ready to turn our attention back to the immediate problem at hand: coming up with viable prototypes for all-gender restrooms that, unlike the legal battles being waged across the United States, did not accept the conventional configuration of paired sex-segregated bathrooms as a given. Design history encouraged us to seek alternatives to the most common and code-compliant approach to all-gender bathrooms—the “single-user” solution. It supplements multi-user men’s and women’s rooms with a single-occupancy, ADA-compliant room equipped with sink and toilet and a sign using words or icons designating it as gender neutral.

A single-user bathroom provides more visual and acoustic privacy than stalls, making it the preferred choice for many (including trans people). An ideal solution from a user’s perspective would be for building owners to build enough of them to meet occupancy fixture counts (i.e. the number of toilets and urinals required by code). This is, however, rarely feasible because of the additional expense and area required to build single rooms rather than stalls, viable only in situations requiring few fixtures (like a small restaurant). Ideally, single-user bathrooms are grouped next to men’s and women’s rooms; sometimes they stand alone, leaving it up to the user to make the effort to find them.

By virtue of being an exception to the sex-segregated norm, the single-user arrangement has serious drawbacks, negatively impacting trans and nonbinary folk but also the general public. Not only does it reinforce the suspect notion of gender identity as an effect of biology, but it exemplifies the prevailing “separate-but-equal” approach to accessibility that caters to people with “special” needs through separate accommodations—entries, ramps and, in this case, isolated rooms—that stigmatize people who deviate from the norm by isolating them. These include trans and gender-nonconforming people as well as people with disabilities who are prevented from mixing with “normal” people in public space.

Stalled! advocates an alternative model that abolishes the binary. We are in favor of getting rid of the typical sex-segregated facilities characterized by American-style stalls whose revealing gaps compromise visual privacy. We recommend a multi-user solution that treats the restroom as a single open space with floor-to-ceiling partitions and communal areas for washing and grooming. Two early examples of this non-code-compliant solution, both located in New York City, were implemented at The Modern, Danny Meyer’s restaurant which opened in 2005 on the ground floor of the Museum of Modern Art, and Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a synagogue for the world’s largest LBGTQ congregation designed by Architecture Research Office (ARO), who built the restrooms by obtaining a variance from the NYC Department of Buildings in 2016.

This solution has two advantages: by consolidating a greater number of people in one, rather than two, rooms, restroom users can visually monitor one another, reducing the risk and fear of violence and ensuring that gender-nonconforming people aren’t stuck between two options that don’t align with their identities. Finally, the multi-user type not only meets the needs of the trans community but also caregivers with gender expressions different than those they care for, such as children, the elderly and the disabled. Arriving upon the desegregated multi-user prototype proved to be a turning point for the Stalled! team. Rather than narrowly focus on gender alone, in the words of Susan Stryker, it allowed “Stalled! to leverage trans visibility” to realize MIXdesign’s intersectional mission predicated on the conviction that democratic societies cultivate respect for human difference by allowing a spectrum of bodies to safely mingle in public spaces regardless of age, gender, religion or ability.

Stalled! favors the multi-user restroom type because it eliminates the gender binary while promoting intersectional mixing and caregiving. However, our team agreed this model could be improved by calling into question the age-old idea that people can be made safe by erecting physical boundaries. Walls are shared two-sided elements that, by definition, belong to the spaces that they divide, located on either side of them. Although often erected to provide security, they can, through ingenuity or force, be breached. For this reason, walls serve a symbolic purpose: in the name of security, they are built to “naturalize” human difference and justify discrimination. For example, President Trump’s contested border wall deploys a physical boundary to construct two oppositional national identities, tainted by misleading stereotypes that bolster far-right agendas. People of color who inhabit the south side of the wall are represented as criminals who threaten to endanger the lives of the white, law-abiding Americans who occupy the wall’s north side. Although they operate at the smaller scale of interiors, the walls found in bathrooms also bring into being a series of oppositional identities that are always already blurred. The corridor wall separates the “clean” public realm from the “dirty” realm of the abject body. The paired entry doors marked men or women operate like the shared walls that typically conjoin back-to-back men’s and women’s rooms: they sort humans into two categories defined by anatomy. Finally, the bounded enclosure of the single-user facility reinforces ableism by compartmentalizing the able from the disabled body.

The privacy screens that subdivide the interior of men’s and women’s restrooms into activity zones form nested enclosures that also obey an ideological rather than a functional logic: placed between urinals and toilets, they are intended to create visual privacy between members of the same sex. However, according to theorist Lee Edelman, in the men’s room, they paradoxically have the opposite effect. The flimsy partitions suspended between urinals, although designed to prohibit looking at one’s neighbor peeing, often trigger anxious feelings of masculine inadequacy and same-sex desire that they were designed to ward off. Likewise, the toilet stall that sequesters men in adjacent compartments, Edelman argues, calls attention to the male orifice they were designed to hide—the anus. For men, this orifice that excretes feces is not only dirty but is capable of being forcefully penetrated, producing sensations of pain or pleasure and as a consequence inducing feelings of ambivalence, anxiety and shame. In other words, the underlying purpose of urinal screens and privacy stalls—to foster a sense of security while at the same time legislating appropriate conduct between men—is confounded by the potential of these architectural elements to elicit conflicting and threatening feelings of abjection, shame and desire.11

Rather than conceive of bathrooms as nested walled enclosures, Stalled! has developed a prototype that eliminates most of the walls and partitions that sort bodies into binary categories by sex (male vs. female), sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. homosexual) and ability (able-bodied vs. disabled). The only partitioned enclosure that remains in our design is the toilet stall itself. Our decision is based on evidence-based research showing that the stall offers many individuals and caregivers acoustic and visual privacy, qualities they desire based on cultural, religious and psychological factors that will be elaborated later in this paper.12

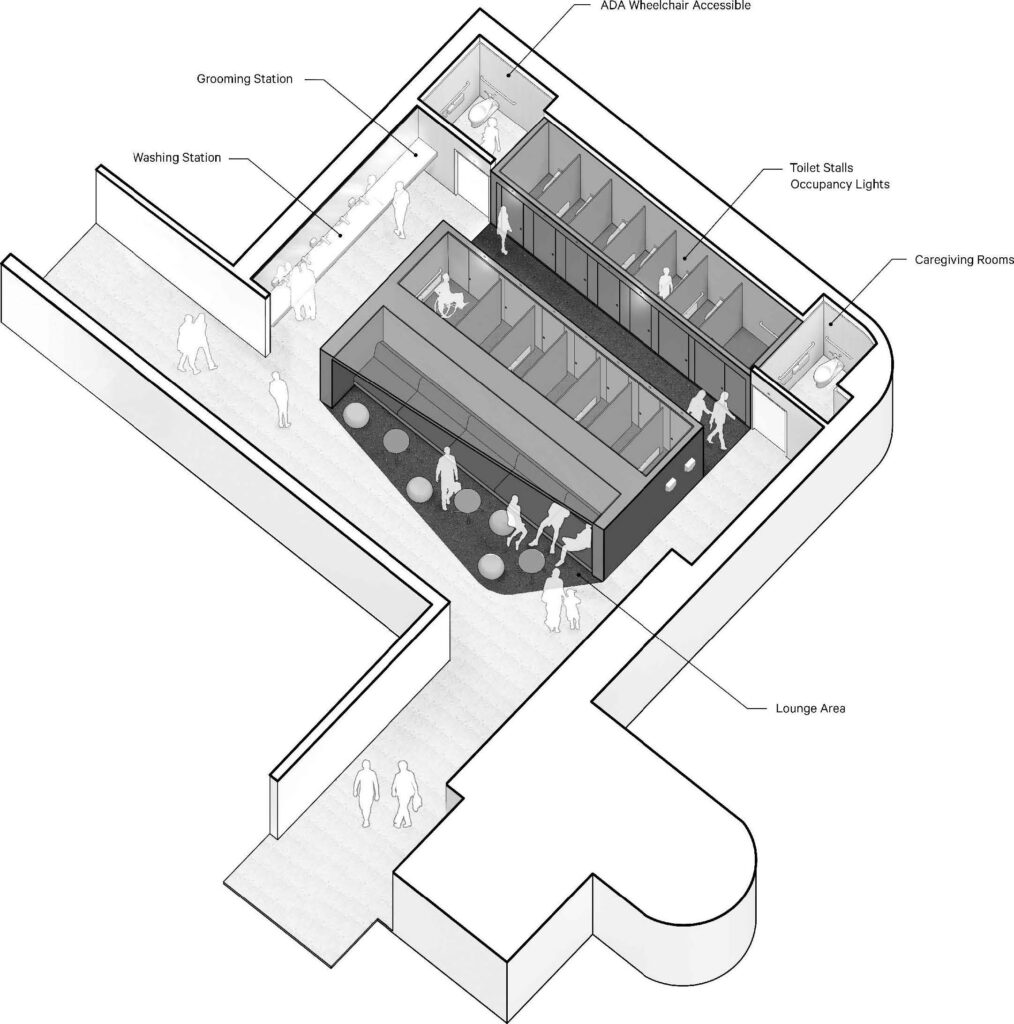

In 2017, we collaborated with Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, a school for the deaf that has been meeting the educational needs of “nonconforming” bodies since its founding by Abraham Lincoln in 1864, to develop a prototype (Figure 8) for retrofitting typical sex-segregated bathrooms into a multi-user facility.

Our case study works within the existing footprint of adjacent men’s and women’s rooms located in the Field House, the university’s sports facility. Drawing inspiration from antique and medieval precedents, our scheme implements a sequence of design moves that reconceives the public restroom as a porous extension of the public realm. First, we removed the existing plumbing stack wall that separated the men’s from the women’s room, treating the bathroom as one open space. Then we eliminated the corridor wall and bathroom doors, allowing the bathroom to blend with the hallway. Next, we added two blocks of fully enclosed stalls of three sizes—standard, ambulatory and ADA—as well as caregiving rooms equipped with a toilet, sink and changing tables that allow for caregiving between people of different genders. Then we added communal grooming and washing areas off the main circulation path. Finally, our scheme takes advantage of the additional square footage gained by removing the corridor wall, transforming what was previously a monotonous hallway into a lounge. It features a high-backed, blue-upholstered banquette, movable stools and a message board, creating a waiting area for caregivers and a place for face-to-face conversations that facilitate deaf signing. Although tailor-made for Gallaudet’s Field house, we eventually posted it on Stalled!’s open-source website as an adaptable prototype. It has become a template that we and other designers have subsequently applied to other commissions.

Figure 8 Gallaudet multi-user facility, drawing by JSA/MIXdesign, 2017.

End-User Engagement through the Lens of Public Health

Soon after completing the Gallaudet project in 2017, we unveiled the Stalled! multi-user prototype at a series of public lectures and symposia at universities across the United States, the UK and Europe. Each event concluded with Q&A sessions where audience members offered valuable feedback that made us aware that our prototype inadvertently ignored many end users’ needs. A person in a wheelchair in Salt Lake City let us know that he faced overlapping but somewhat different mobility challenges from users of canes, crutches and strollers that might require more nuanced spatial solutions than provided in our designs. At an event in New York City, a Muslim woman politely pointed out that while she was sympathetic with our intention to promote sharing, our scheme could not accommodate women like herself. Certain Muslim women, such as the one giving us feedback, wear modesty garments that cover everything except the face and hands up to the wrists, making washing in the presence of men an impossible task. Meanwhile, audience members in other venues we visited pointed out that our prototype did not take into account the wide variety of practices that take place in public bathrooms but that go unspoken. Examples mentioned included people who administer insulin injections, people (including trans men) who menstruate, people who suffer from shy bladder syndrome and religious people who perform ablutions. How could MIXdesign reconcile our mission to promote mixing in public space in a way that avoided siloing people into reductive categories? How could we accommodate the many varieties of being human inflected by culture, gender and ability? How could we steer clear of one-size-fits-all architectural solutions and come up with flexible prototypes that can be adapted to meet the needs of different demographic communities for different sites and programmatic scenarios?

Taking Stalled! on the road proved to be a wake-up call. We realized that our team was not qualified to address these complex issues on our own. Through a combination of deliberate networking and serendipity, we were able to expand our team to include clinicians, physicians and administrators with expertise in medicine, public health, deaf space, accessibility, neurodiversity and religion. Collectively, they worked with us to refine our research methodology in a way that allowed us to study the needs of wider segments of the population overlooked in typical restrooms.

For example, in 2019, Stalled! enlisted the help of members of the Yale School of Public Health. Antonia Caba, a graduate student working under the supervision of Professor John Pachankis, conducted surveys, interviews and a comprehensive literature review to gain an understanding of the specific cultural, psychological and medical needs of an expanded list of restroom end-user groups. Antonia organized them into loose overlapping categories, including gender (trans and nonbinary, pregnant and breastfeeding people, people who menstruate), disability (people with mobility, sensory and neurodiversity challenges, including the deaf and hard of hearing, the blind and those with low vision and individuals with autism), medical and psychological conditions (bowel and bladder conditions such as shy bladder syndrome), religion (Muslims and Orthodox Jews) and caregivers of children and adults.

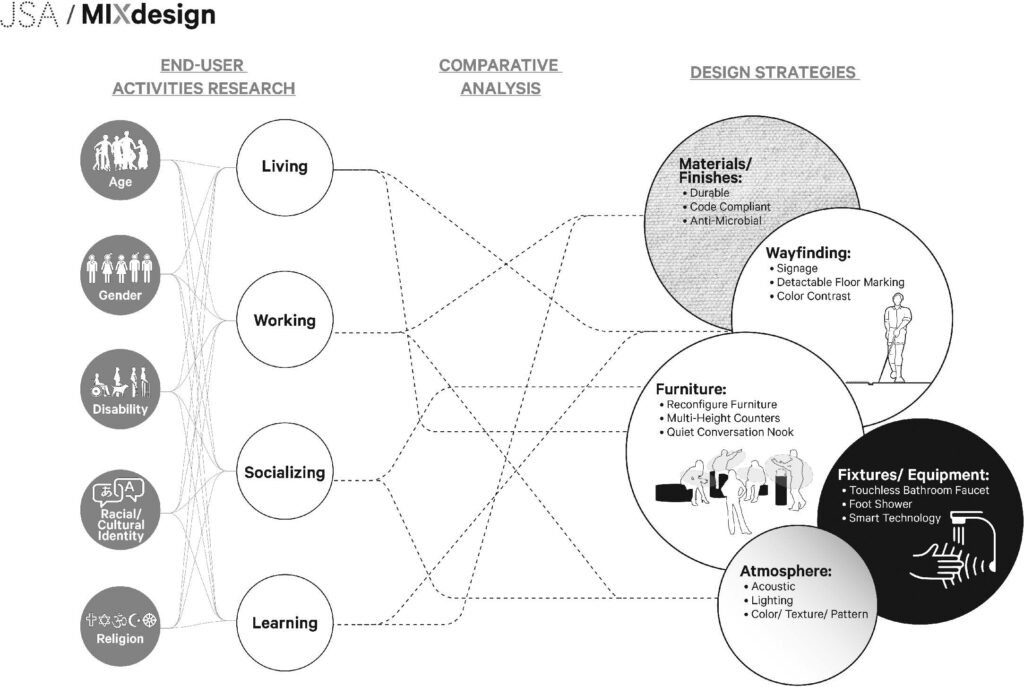

We knew from the outset that creating one bathroom with zones dedicated to each user group would be spatially and economically unfeasible. Instead, our expanded team developed an aspect of our methodology (Figure 9) that we now apply to other MIXdesign projects: we conduct a comparative analysis of different user groups that yields a matrix that charts the overlapping and sometimes conflicting needs of noncompliant end users. This data informs our design process, allowing us to generate design recommendations which promote sharing among differently embodied and identified people while also satisfying end users with unique functional or privacy needs.

Figure 9 Inclusive design methodology, drawing by JSA/MIXdesign, 2017.

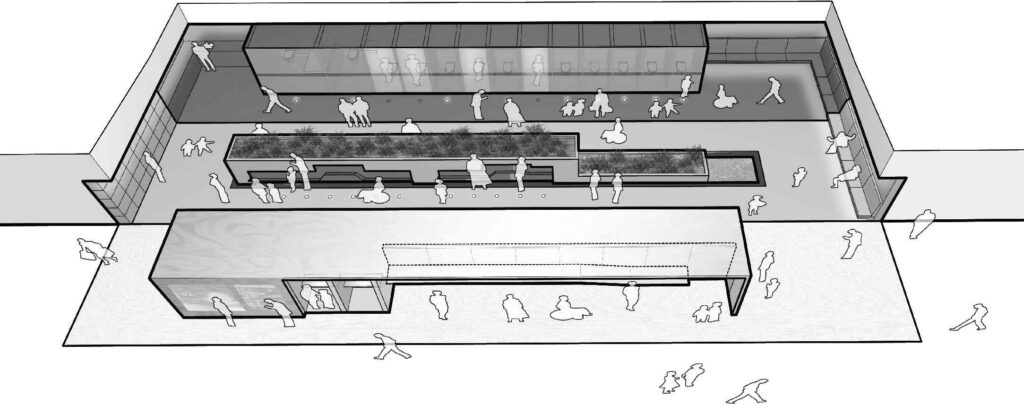

Figure 10 Stalled! airport prototype, aerial view, drawing by JSA/MIXdesign, 2017.

We applied this new body of research conducted in collaboration with Yale Public Health to another Stalled! prototype for larger high-traffic spaces, like airports (Figure 10). Working with the footprint of the typical back-to-back sex-segregated restroom as depicted in airport planning manuals, we reconceived of the public restroom as an open, agora-like precinct adjacent to the main concourse animated by three parallel activity zones, dedicated respectively to grooming, washing and eliminating. Slip-resistant sheets of diamond plate, tile and rubber differentiate each of the three activity zones, which are colored a different shade of blue for those with low vision. Immediately adjacent to the concourse, a mirrored wall captures the reflections of multiple users who groom at a multi-level dry counter that serves people of different heights and abilities.

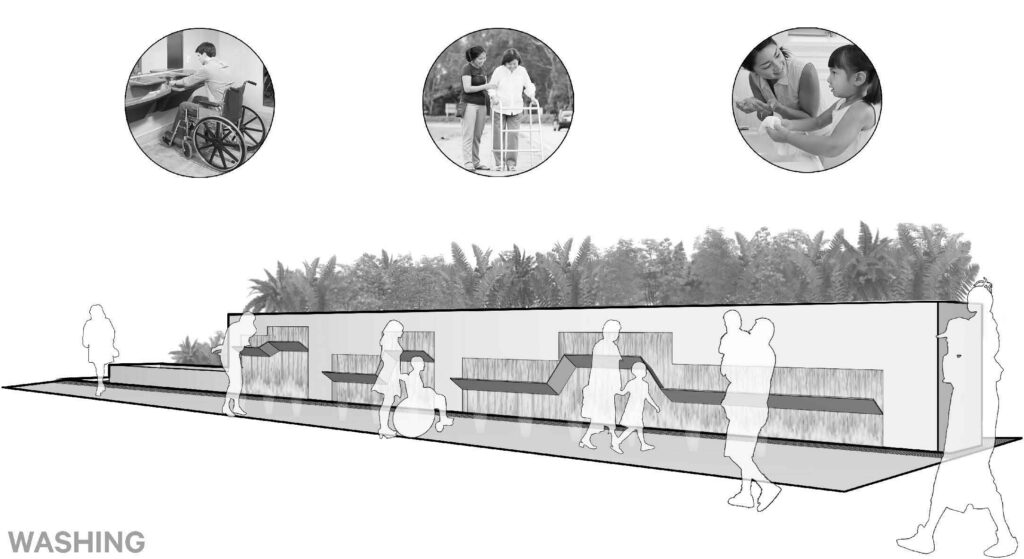

Those who want privacy can retreat into curtained alcoves for breastfeeding, meditation and prayer and administering medical procedures such as insulin injections. Adults, children and people in wheelchairs wash at a communal water wall (Figure 11). Inset floor lights indicate the location of motion-activated faucets that allow water to flow into an inclined splash plane placed at different ergonomic heights; the water is then collected and cleaned in a remediating planter before being recycled. The scent of plants and the ambient sounds of flowing water mask bodily sounds and odors, two factors that inhibit modest people, including those with shy bladders, from using public restrooms.13 13 The back of the space is occupied by rows of toilet stalls, including caregiving stalls that are equipped with adult changing tables and foot showers for ablutions. As users circulate from one station to the next, passing from the outermost grooming station to the innermost toilet wall, they experience a multi-sensory gradient that takes them from public to private, open to closed, dry to wet, smooth to slip resistant, acoustically reverberant to sound absorptive, ambient to spot lighting.

Figure 11 Stalled! airport prototype, washing station, drawing by JSA/MIXdesign, 2017.

Designing inclusive bathroom prototypes is one thing; implementing them is another. In 2018 MIXdesign was launched as a consultancy to respond to inquiries from institutions wanting to implement the multi-user prototype we advocated. However, we soon learned that building codes legislating sex-segregated restrooms presented an obstacle to their realization. Building them requires a variance, the outcome of a time-consuming process with unpredictable results that can discourage even the most motivated clients from implementing them. Our team realized that we needed to take legal matters into our own hands. Making the multi-user type viable meant amending the International Plumbing Code (IPC)—the model code that regulates the design and installation of plumbing systems in all types of buildings. Under the leadership of Terry Kogan, we joined forces with the American Institute of Architects, the National Center for Transgender Equality and the law firm of Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner in 2018. Our lobbying efforts were successful: the amended version of the code will appear in the 2021 version of the IPC and will be available for adoption by local, state and federal governments. Stalled! is especially proud of this victory. For us it exemplifies the potential for designers to expand their reach beyond discrete design commissions and form cross-disciplinary alliances that challenge and redefine the overall legal frameworks that shape the design of building and cities.

The inclusive design approach that informed Stalled! is an ongoing work in progress, as is the Stalled! project itself. MIXdesign, in collaboration with our network of experts, is refining the methodology as we apply it to other building types, including university campuses, museums and housing. Conducting cross-disciplinary research that interrogates design standards through a critical lens remains central to our approach, predicated on our conviction that designers can no longer turn a blind eye to the way the seemingly innocent conventions of architecture reproduce and perpetuate heteronormativity, structural racism and ableism. The creation of welcoming public spaces that foster social equity, health and wellbeing depends on first identifying and then overcoming the deep-seated historical and ideological forces that have shaped the design of everyday built environments. Raising awareness of how the protocols of professional practice transmitted through architectural typologies, standards, legislation and building codes produce noncompliant bodies is, in part, a historical project. Moving forward means looking back. History examined through a critical lens can be an instrumental tool in the realization of alternative futures—a testimony that the future can be different than the present, just as the present is different from the past.

Bibliography

Cahill, S. E., W. Distler, C. Lachowetz, A. Meaney, R. Tarallo, and T. Willard. “Meanwhile Backstage: Public Bathrooms and the Interaction Order.” Urban Life 14, no. 1 (1985): 33–58.

Cogdell, Christina. Eugenic Design: Streamlining America in the 1930s. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. New York: Routledge, 1966.

Edelman, Lee. “Men’s Room.” STUD: Architectures of Masculinity. Edited by Joel Sanders. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Elizabeth, Grosz. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Kogan, Terry. “Sex-Separation in Public Restrooms: Law Architecture, and Gender.” Michigan Journal of Law 14, no. 1 (2007): 1–58.

Kosso, Cynthia, and Anne Scott, eds. The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing and Hygiene from Antiquity through the Renaissance. Boston, MA: Brill, 2009.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Molesworth, Helen. “Bathrooms and Kitchens: Cleaning House with Duchamp.” In Plumbing: Sounding Modern Architecture, edited by Nadair Lahji and D.S. Friedman. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997

Development and Validation of the Shy Bladder Scale. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 41, no. 3: 251–60.

Serlin, David. “Pissing without Pity.” In Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing. New York: New York University Press, 2020.

Trump administration impacting the rights of trans and LGBT people. https://transequality.org/the-discrimination-administration.

U.S. Transgender Survey, prepared by National Center of Transgender Equality, 2015, pp. 14-15.

Notes

- There are a number of scholarly works examining the impacts of eugenics. See, for example: Christina Cogdell, Eugenic Design: Streamlining America in the 1930s (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). ↩

- However, while this essay presents this process as a linear narrative, the design process is never so logical and straightforward. Each phase of the project involves conducting parallel and overlapping tasks that sometimes require us to circle back and conduct additional research or reconsider assumptions we had made earlier. ↩

- According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, there are over 70 documented actions taken by the Trump administration impacting the rights of trans and LGBTQ people. https://transequality.org/the-discrimination-administration. ↩

- Terry Kogan, “Sex-Separation in Public Restrooms: Law Architecture, and Gender,” Michigan Journal of Law 14, no. 1 (2007): 1–58. ↩

- David Serlin, “Pissing without Pity,” in Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814759646-016. ↩

- U.S. Transgender Survey, prepared by National Center of Transgender Equality, 2015, 14/15. ↩

- Cynthia Kosso and Anne Scott, eds., The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing and Hygiene from Antiquity through the Renaissance (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2009). ↩

- Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Nota, 1982); Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (Routledge, 1966); Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Indiana University Press, 1994). ↩

- Helen Molesworth, “Bathrooms and Kitchens: Cleaning House with Duchamp,” in Plumbing: Sounding Modern Architecture, eds. Nadair Lahji and D. S. Friedman (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997). ↩

- Kogan, “Sex-Separation in Public Restrooms.” ↩

- Lee Edelman, “Men’s Room,” in STUD: Architectures of Masculinity, ed. Joel Sanders (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996). ↩

- S. E. Cahill, W. Distler, C. Lachowetz, A. Meaney, R. Tarallo, and T. Willard, “Meanwhile Backstage: Public Bathrooms and the Interaction Order,” Urban Life 14, no. 1 (1985): 33–58. ↩

- Paruresis (shy bladder syndrome) is categorized as a social phobia rather than a functional disorder. Symptoms can include fear of others hearing or smelling urination. See B. Deacon, J. Lickel, J. Abramowitz, and P. McGrath, “Development and Validation of the Shy Bladder Scale,” Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 41, no. 3 (2012): 251–60. ↩

Activity zones: Treating the toilet stall as a privacy unit allows us to eliminate the barrier that typically divides adjacent men’s and women’s rooms as well as the wall that separates them from the concourse and instead reconceive of the public restroom as a semi-open agora-like precinct that is animated by three parallel activity zones, each dedicated to grooming, washing, and eliminating.

Activity zones: Treating the toilet stall as a privacy unit allows us to eliminate the barrier that typically divides adjacent men’s and women’s rooms as well as the wall that separates them from the concourse and instead reconceive of the public restroom as a semi-open agora-like precinct that is animated by three parallel activity zones, each dedicated to grooming, washing, and eliminating.